On 15 Sept 1993 Father Guiseppe ‘Pino’ Puglisi was returning to his parish of San Gaetano in Brancaccio, a poor suburb of Palermo. As he got out of his car two men approached. They were Cosa Nostra hitmen. Shooter Salvatore Grigoli later admitted that Puglisi’s last words were ‘I’ve been expecting you.’ He was killed by a single bullet fired at point blank range.

And Father Puglisi’s crime? The 56-year-old priest, a native Brancaccio, had returned to the place of his birth in 1990. For the next three years Puglisi railed against the criminality of the local mafiosi and the code of omerte (silence) which protected them. He further humiliated the mafiosi by banning them from leading religious parades.

Albeit appalling Puglisi’s murder came close to the end of the period known as the ‘Years of Lead’. Four years after the slaying of Father Puglisi, beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in May 2013, the Graviano brothers were arrested and later imprisoned for life for the Puglisi murder and the anti-government bombings that killed 10 people in bombings Florence, Milan and Rome.

The Florentine attack became particularly notorious. Six months before the Puglisi murder, mafiosi had placed a car loaded with 250kg of explosive underneath the Georgofili Academy in Forence. Apart from killing five civilians, damaged was done to the Plazzo Vecchio and the Uffizi Gallery where master paintings were destroyed. As President Meloni noted on the 30th anniversary of the Georgofili bombing in May this year,

“No Florentine, no Italian, will ever be able to forget the Georgofili bombing, just as no one can ever erase from memory those years that were so difficult for our nation, marred by other bloody attacks and massacres.”

In assessing the 35-year period known as the ‘Years of Lead’ one man stands out as the dominant villain of the period. Salvatore ‘Toto the Short’ Riina was the notoriously violent head of the Corleonesi gang that dominated the Sicily’s Cosa Nostra during this most violent phase of post-war Sicilian gangsterism. Also known as la Belva (the beast) and Il Capo dei Capi (the boss of bosses) Riina had come to the fore in Corleone, a town in central Sicily, in the late 1950s. Along with Bernardo Provenzano and Calogero Bagarella, Riina was one of a trio of gunmen who expanded the power of his famously brutal Corleonesi crime syndicate.

In December 1969, after the First Mafia War that had begun seven years earlier, Riina was the senior mafia figure chosen to organise the killing of mafia boss Michele Cavataio. His execution had been ordered after a meeting of mob bosses in Zurich. It had been called for by Salvatore ‘little bird’ Greco who had travelled from his hiding place in Venezuela. Greco had been the first post-war head of the mafia ‘commission’.

Formed by Sicilian and New York Mafia, the commission included legendary figures such as New York gangster Lucky Luciano. They had met at the Hotel Delle Palme in October 1957. As I noted on my recent visit, the bar at the Palme is still the place to be seen on a Saturday evening for the city’s high rollers – mafiosi included one suspects.

Cavataio’s crime was that he had orchestrated the First Mafia War to get two rival gangs to fight each other. Riina’s soldiers entered the offices of the Girolamo Moncada construction company where Cavataio, his sons, the builder and their accountant were meeting. Within seconds, 108 rounds were fired leaving five men dead; it became known as Viale Lazio Massacre. The wounded Cavataio was clubbed unconscious by the renowned killer Bernado Provenzano when his Beretta 38/A machine gun jammed. He then shot Cavataio with a pistol. Corleonesi gunman Bagarella was killed in the exchange and was taken away and secretly buried in Corleone.

Riina may have ended the First Mafia War but he was instrumental in starting the Second Mafia War, 1981 – 1984, sometimes known as the Great Mafia war. (It was a case of life imitating art; Francis Ford Coppola’s film ‘The Godfather’ about the fictional Corleone family was made a decade earlier in 1972). By the mid 70s Riina had become boss of the Corleonesi. He determined to takeover from the dominant Palermo gangs. The resulting war brought over 400 killings in Palermo and a similar number throughout Sicily.

It was in reaction to the bloodletting of the Second Mafia War that Cabinieri General, Carlo Alberto della Chiesa was chosen as the prefect of Palermo in 1982 with a specific brief to defeat the mafia. In the 1970s he had successfully combatted the Red Brigades in northern Italy; with the help of Silvano Girotto, Fatre Mitra (the machine gun friar), the former monk who infiltrated the Marxist terrorist group, Chiesa had captured the key terrorist leaders.

There was much optimism therefore when Chiesa was appointed in 1982 as prefect of the Palermo region with a specific anti-mafia brief. It was a short-lived reign. Six months after his appointment Chiesa was driving his wife out for dinner when two gangsters, armed with AK47s drove up alongside his modest Autobianchi car and sprayed it with bullets. Chiesa and his wife were killed along with a tailing bodyguard.

Despite these setbacks, fearless police, journalists and judges, many of whom were murdered, continued to bear down on the Mafia. In 1986 prosecutors, including Giovanni Falcone and Paulo Borsellino, managed to convict 338 mafiosi in the so-called Maxi Trial. Riina and Provenzano, who were convicted in absentia, went into hiding but continued to run their drug, construction and extortion operations.

They were the architects of the murder of anti-mafia judges Giovanni Falcone and his friend Paolo Borsellino blown up by bombs under their cars in May and July 1992 respectively. In recent years it has been reported that John Gotti, head of New York’s Gambino family sent explosive experts from the US to help the Corleonesi.

Earlier in the year mafia politician Salvo Lima, a Christian Democrat member of the European Parliament, a former cabinet minister and mayor of Palermo, closely associated with Giulio Andreotti, a 7-time prime minister, was murdered for reputedly failing to reverse the in-absentia judgements against Riina. Lima, whose father was an important mafiosi, may well have been a ‘made man’ himself. Lima had the luxury of never having to break sweat in campaigning for the offices to which he was elected throughout his political career.

However, the roundup of hundreds of known mafiosi following these atrocities effectively ended the ‘Years of Lead’. The supposedly in-hiding Riina was arrested while comfortably ensconced at home in his villa in Palermo on 15 January 1993.

Riina and other of the arrested senior mafiosi were put in ‘special’ solitary isolation known as ’41-bis’, after an article of the 1975 Italian Prison Administration Act. The one-hour allowance for exercise and closely monitored once monthly family visits, made management of their operations from prison virtually impossible. Riina had taken on the Italian state in almost open warfare and had lost.

On the face of it may have seemed that with Riina’s arrest, the Mafia had been largely expunged from Sicilian life. Historically the organisation, sometimes known as ‘la tradizione’ had for centuries operated as a shadow government or at least as shadow factions. Proto-mafiosi, in the form of criminal ruffians were employed in the wars between the noble families of the Luna and Perollo between 1455 and 1529. Later in the hundred-year pre-risorgimento (Italian unification) phase of Sicilian history, mafiosi were employed by aristocratic factions as well as their populist opponents.

Even the Catholic church has from time to time worked with the mafia, particularly against leftist organisations. In 1960 Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini, who had ordained Father Puglisi, questioned the very existence of the Mafia. When asked by a journalist about the mafia, he joked, ‘so far as I know it could be a brand of detergent.’ Ruffini was known to regard communism as a much greater threat to society than a mafia, that was always deeply reverent of the Catholic Church.

It did not help that in the post war period the US Army often replaced anti-mafia mayors with mafiosi. Even the OSS (the forerunner of the CIA) enjoyed co-operative relations with the Cosa Nostra. It was an organisation that was woven into the fabric of Sicilian life. As British historian, Tim Newark, has explained in The Mafia at War [2007], the traditions of the ‘men of honour’,

“developed in reaction to centuries of foreign invaders who had come to Sicily – the Greeks, Romans, Moors, Normans and Spanish. Prevented from participating in the rule of their own land, Sicilians depended on their own extended families for justice and assistance.”

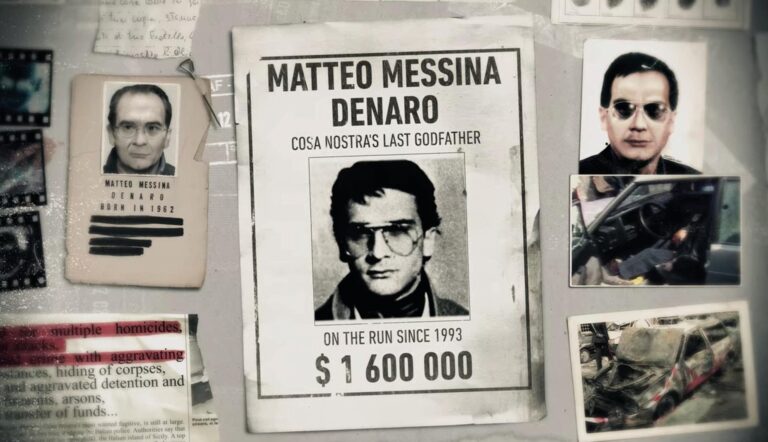

Although the Sicilian mafia may have gone quiet after the incarceration of Riina in 1993 it did not disappear. The notorious killer Bernardo Provenzano succeeded him as capo di capi. Provenzano, a religious fanatic sometimes known to dress as a cardinal, ordered an end to political killings and the war on the state. However, he continued to control the mafia’s criminal operations until his arrest in 2006. Subsequently the reins passed to Mateo ‘Diabolik’ Denaro.

Famed as a youthful gunman who boasted of having ‘filled a cemetery all by myself’, Denaro was a womanising playboy with a penchant for fast cars, expensive watches and Versace clothes. During his tenure he helped move the Cosa Nostra away from violent gangsterism toward legitimate business and corporate infiltration. Supposedly the Cosa Nostra has gone ‘green’ and is a major beneficiary of Italy’s subsidisation of Sicily’s wind farms. After a European wide manhunt over 30 years, Denaro, estimated to be worth Euros 4bn, was finally arrested on 15 January this year, and died of cancer six months later.

It remains to be uncovered who has succeeded him. Some have described Denaro’s death as the end of an era. That seems improbable. For centuries Sicily’s mafia has morphed with the times. It will continue to do so. Judging how clam-shut Sicilians were about the mafia when I raised it in conversation, it seems clear that the tradition of omerte is alive and well. There is a very good reason for that.