Kong Fuzi, more commonly known as “Confucius,” was a champion of social harmony and humanism. For more than two and half thousand years, his wisdom informed Chinese society, politics, and culture. That is until Communism took root. Chairman Mao Zedong denounced Confucianism as “regressive, pedant, and feudal” and the cause of China’s contemporary weakness.

But Mao's brutal Cultural Revolution failed to crush Confucius’ legacy. Indeed, Confucius expert Professor Daniel Bell argues that the previously disparaged philosophy has staged a “dramatic” comeback.

As a former dean of the School of Political Science and Public Administration at Shandong University, the Canadian academic holds a place of exceptional honor, especially for a non-Chinese.

In his book, The Dean of Shandong: Confessions of a Minor Bureaucrat in Shandong Province, he recounts his extraordinary tenure. Now an instructor at the University of Hong Kong, Bell explains to Die Weltwoche how the wisdom of the ancient sage shapes today’s Chinese society and politics.

“Struggle at the higher levels”: Professor Daniel Bell

“Struggle at the higher levels”: Professor Daniel Bell

Weltwoche: Professor Bell, why is Confucianism a key to understanding contemporary China?

Daniel Bell: Because Confucianism is the main political tradition of China that has had great influence in shaping the political institutions, as well as the political ideals that shaped Chinese history that continue to shape it, now.

Weltwoche: Confucianism is described as a belief system which focuses on the importance of personal ethics and morality based on Confucius who lived 2,500 years ago. How has it gained such an eminent role throughout China’s history?

Bell: There are two things about Confucianism. First, it's a very political tradition, but it was only about 500 years after the death of Confucius that it became a kind of official value system. It took a long time. Until then, it was very much a philosophy and a very critical philosophy that was used by intellectuals — most famously Mencius and Xunzi — to critically evaluate the dominant ideals at the time. In the Han Dynasty, finally, Confucianism became an official value system endorsed by the emperor, and it shaped the official education for the public officials almost until the collapse of the imperial system in 1911, 1912.

That's one level. It's very much a political tradition, but it's also very much a philosophical tradition — one that has been carried forth by intellectuals since the time of Confucius, himself, to shed critical light on the political system. If you're a Confucian, you owe your allegiance, first and foremost, not to the status quo but to the Dao, this moral way that is used as a basis for evaluating the political reality. So, on the one hand, it's a very political tradition. On the other hand, it's also a very critical philosophical tradition.

Weltwoche: Before we dive deeper into the essence of Confucianism, what do we know of its founder?

Bell: Confucius (551 – 479 BC) was kind of a failed political advisor. This was before China was unified. He roamed from state to state, hoping to persuade rulers to adopt his views of, let's call it, “political morality.” But they weren't receptive. He went back to his home state of Lu, which is in contemporary Shandong province, and settled for the life of a teacher almost as a second choice. Fortunately for us, he was a great teacher, and he had it's estimated up to 3,000 students of whom 72 became close followers.

If you go to China, now, including the hometown of Confucius, Qufu, in Shandong province, he's remembered as a teacher, as a teacher for 10,000 generations. He's venerated first and foremost as a teacher of teachers.

Weltwoche: Unlike Christianity or other religions, Confucianism is very much rooted in today's world.

Bell: Confucianism is very diverse, but there's hardly anything about the afterlife. They say this life is too complicated, too complex. Let's try to understand what goes on, here, before thinking about the world of ghosts and so on.

Weltwoche: A core commitment of Confucianism is, that “The good life involves the pursuit of compassionate, harmonious social relation starting with the family and extending outwards.” Where does this focus on the family come from?

Bell: Confucianism, from its very beginning, argued that we learn about morality through the family. The family is a very important sphere of morality. This is where we learn about care and compassion which we then extend outside the family. That's where the good life lies.

It contrasts the ancient Greek tradition. For Aristotle, for example, the good life lies outside the family, and the family is a sphere of necessity. The good life lies in the public. For Confucianism, it's never that. In Confucianism, you have to first have harmonious and compassionate relations with the family. If that works, for one thing, you can more or less predict that the rest of society will be stable.

Confucianism is very important for ethical purposes to focus on the family, but it also has political implications because the state has a very strong obligation to protect and nourish the family through different policies. Even today, like in most of the countries influenced by Confucian heritage, there are various policies that are family friendly. For example, here, I'm in Hong Kong where half of the people live in public housing. If you live with your elderly parents, then you get a tax break.

Weltwoche: So, the high reverence for parents and elders, which is very important in China, comes from Confucianism?

Bell: In Confucianism, a central value is filial piety which means reverence for elderly parents and ancestors. That's viewed as central to the Confucian tradition and influences, today. In mainland China, too, if you don't provide financial resources for your elderly parents, you can literally be taken to court by your parents. It does happen sometimes.

In the West, there's a kind of assumption that we should love our parents. That's a great thing. If, at the age of adulthood, 18, things might happen and it's time to sharpen the separation with the family, then you can do that. In Confucianism, there's no moment of separation like that. That's not to say that Confucians encourage blind obedience to the family. Quite the opposite. Many of the great texts in the Confucian tradition say that if your parents — they even address it to young children— do something morally wrong, you should criticize them. If they don't accept, then wait for the right moment again. Wait till they're in a good mood, and then try again. If that doesn't work, then you cry and you work on their emotions.

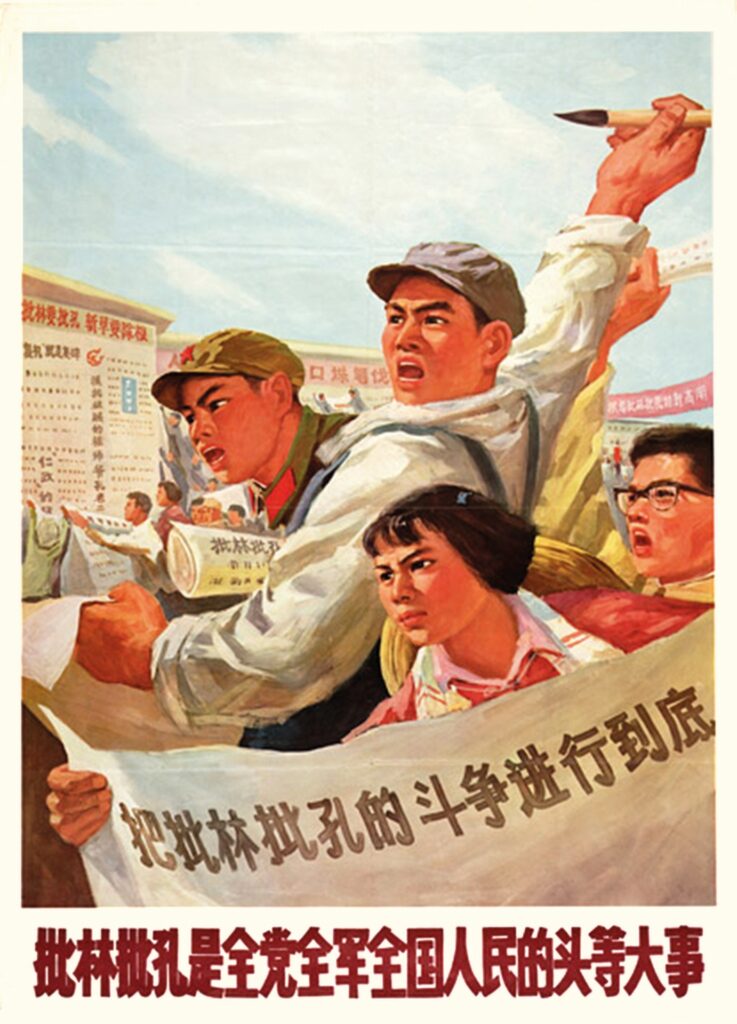

“Regressive, pedant, and feudal”: Mao’s propaganda war against Confucianism

“Regressive, pedant, and feudal”: Mao’s propaganda war against Confucianism

Weltwoche: When the Communist Party took power in the Chinese Revolution in 1949, it blamed Confucianism for the country’s backwardness. Mao denounced it as a “regressive, pedant, and feudal”. He launched the “Criticize Confucius Campaign” which lasted from 1973 until the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1976. Why were Mao and the Communists fighting this tradition of 2000 years so fanatically?

Bell: The denouncement of Confucianism really started before the Communists with the May Fourth 1919 movement which affirmed values like democracy and science. The movement said that for China to modernize it has to basically westernize because the Western countries were the most modern; China has to abandon our so-called feudal traditions, including Confucianism, which contribute to our backwardness in economic and military [matters].

That influenced, eventually, not just the Marxists. The liberals at the time in China also were very critical of Confucianism. The most famous novelist and short story writer, Lu Xun, was very critical of Confucianism. This was a dominant view throughout most of the 20th century, when the dominant tradition was the anti-traditionalism. And it took full form in the Cultural Revolution which was an attempt — almost like the French Revolution — to destroy everything old which was viewed as backward and feudal; we need to have a brand new society that, literally, owes nothing to the past and to tradition. The Cultural Revolution is widely viewed as a disaster. In retrospect, the Chinese leadership realized that Confucianism was often wrongly blamed for China's economic and military backwardness.

Weltwoche: There is another dominant tradition in Chinese politics which is key to understanding contemporary China: Legalism. Over the Chinese history, Legalism comes to the fore in times of chaos. What is the role of Legalism vis-a-vis Confucianism?

Bell: Legalism goes way back before China was unified, in the Warring States Period (475–221 BC) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warring_States_period. Basically, this is the view that the purpose of politics is to strengthen the state. The way to do that is to have harsh laws that control people and punish people for doing bad things and also to have different administrative means of controlling ministers so that they don't try to challenge the ruler. It was, basically, a recipe for a kind of totalitarian society where everybody, more or less, does what they're supposed to do, as specified by the ruler and his laws.

Weltwoche: You've referred to Legalism as a “super Machiavellian,” completely amoral school of thinking.

Bell: Yes, completely amoral. Whatever works to strengthen the state is justified. For the Legalists, the early Legalists, very cruel means are absolutely justified because they're necessary. But they were writing during the worst time in Chinese history. There was bloody battle after bloody battle. The Legalist says the only way to win in that context is to have objective ways of measuring success on the battlefield which they measured by the number of heads of decapitated enemy soldiers. That strategy was used, more or less, to unify China, according to Legalist principles. It was a very short-lived first dynasty. It lasted only about 15 years and collapsed, probably because, or at least in part, because of its excessive cruelty.

Weltwoche: What is the role of Legalism in contemporary China?

Bell: Legalism was marginalized for like 2,000 years because it was viewed as too cruel, amoral, Machiavellian, and so on. It came back to the fore in the 20th century, when China was in this horrible period: bullied by foreign powers; total civil war at home; parts of the country breaking off and declaring independence. It's in that context that the Communists, led by Mao, eventually succeeded. Mao was very much inspired by the Legalists. He said that, in this context, we need to have these extremely harsh means of unifying the country and strengthening the state.

Arguably, it made a little bit of sense in that context, but in times of peace and development, obviously, this Legalism is counterproductive. You want some diversity in society. You want people to express their views and to have their own ideas for developing personally and for developing the society. Also, people have to be responsible and have some sort of morality that informs what they do and constrains their bad actions.

That also helps to explain why Confucianism has made a dramatic comeback since then: because it's the most obvious resource for thinking about how China could develop in a peaceful way.

Weltwoche: In the past 30 years Confucianism has been embraced by Chinse leadership. After taking power, President Xi Jinping said, in 2014, that Confucius represented rational thinking. China’s ruling Communist Party now hails Confucius as a symbol of Chinese culture. At the same time, Chinese leadership has not renounced Marxism. How does the age old tradition of Confucianism square with Marx’s teachings?

Bell: The ruling organization, of course, is officially Marxist, but people know, political reformers, that Marxism is not sufficient to inspire people, anymore. I think the Communist tradition is making a bit of a comeback, as well, but it's not sufficient. That's why the ruling organization now identifies with a much longer tradition, including imperial China, and it views itself as a carrier of this longer tradition. Since Confucianism was a central political value system of imperial China, then it makes sense to appeal to Confucianism for political legitimacy in contemporary China, as well. That's part of the story. It’s very much a political story. It's a way of supplementing, let's call it, the values-based legitimacy of the state.

The other hugely important reason is it's not just about China. Other countries with a Confucian heritage in East Asia also modernized quite rapidly and peacefully, including South Korea, Japan, and Vietnam, and Singapore. Then, so many intellectuals came to realize that this worldly outlook (of Confucianism) and its commitment to future generations, to work hard and a constant quest for self-improvement and education — that all these values are actually quite compatible and help to bring about modernization in the modern world, so long as other conditions are in place.

Weltwoche: There is a downside to modernity — that it makes people very individualistic and there's a need to reaffirm social responsibility. Promoters of Confucianism say that this is where Confucius teachings, too, has a ready answer.

Bell: Because it strongly emphasizes responsibility to others, starting from the family and extending to others. That's another reason why it's being taught in schools and so on, because there's a need to promote more responsibility in society.

It's very interesting, too, that many of the same intellectuals, when they were young, were forced to read Confucianism in order to denounce it in the Cultural Revolution, but then they realized when they were doing that, "Hey, this tradition is actually much more interesting than officially advertised," so to speak. Once the conditions allowed for more free expression, this respect, then these same intellectuals became the promoters of Confucianism.

Perhaps the most clear example is Jiang Qing. He's perhaps the leading political Confucianism in China now. He has his own independently funded academy in remote Guizhou province, and he learned about Confucianism in the Cultural Revolution in order to denounce it. Then, of course, if you're smart and you have your own mind, and which he did, and now he's the leading promoter of Confucianism.

Weltwoche: How does Confucian thinking influence Chinese policymaking, today?

Bell: I don't want to say that if you want to understand Chinese foreign policy, you have to look at the ancient texts of Confucians. Obviously, other traditions and value systems and sometimes amoral systems, like Legalism, play a role. If you're working in the security or military apparatus in China, you're more likely to look to the Legalist tradition for inspiration. Of course, they're not the only ones who have a say. On issues like foreign policy, the Confucian tradition has had a long history of thinking about morally justified war or what we call “just war.” Other than Confucians themselves, the most influential Confucian is Mencius.

Weltwoche: Mencius (372–289 BC) has often been described as the "Second Sage," that is, second to Confucius, himself.

Bell: He was writing in the Warring States Period. A text opens where he's directly criticizing one of the rulers for launching unjust wars just for the sake of capturing territory and enriching himself. Mencius says, "No, if you want to carry out a morally justified war, certain conditions have to be in place. It has to be purely defensive.” If it is somewhat offensive, then it has to be, what we would call today, “humanitarian intervention.” That view is essential today, and it's taught in Chinese military academies. It helps explain, while we can be cynical and so on, why China hasn't gone to war since 1979.

Weltwoche: And where does Confucianism come into play in China’s contemporary diplomacy?

Bell: Especially in imperial China, the idea was emphasized that, when you're engaging with other countries, it has to be reciprocal or a win-win, so to speak. Of course, that's a contemporary rhetoric, let's say, in the Belt and Road Initiative. But it goes way back in imperial China when, for most of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) and Qing dynasty (1644 bis 1911), China had a kind of tributary relation with Korea, but it was mutually beneficial. In fact, economically speaking, it benefited Korea more than China. Korea would pay symbolic tribute to China, and China would provide economic benefits to Korea.

Now, of course, we don't do that, today because, at least in principle, all the states are supposed to be equal. But, in practice, I think China, maybe more than other countries, recognizes that there's a hierarchy of states and that China has more power because of its size and population and influence but, when it carries out foreign policy, it should do it in a way that benefits not just itself but the weaker countries.

We can be cynical — and, certainly, the Legalist would be against that — but it's essential to the Confucian tradition. There is that struggle at the higher levels of the Chinese government: which tradition should matter more. But so long as the Confucian tradition is viable and has some degree of influence, I think we should not be completely cynical about Chinese foreign policy.

Weltwoche: It was quite extraordinary that you, as a non-Chinese, were appointed as dean at the Shandong University to teach Confucianism. Do you see this as evidence for the renaissance of Confucianism and the transformation of higher education?

Bell: I don't want to overestimate my importance, but let's just say it's one data point which reflects on the openness. It's not just about Confucianism. I worked in China in higher education for nearly three decades, and almost every intellectual or academic wants more academic freedom, wants more international exchange. Many of them are Party members. Almost all the leaders are Party members, I know from personal experience. Certainly, in academia, there's this huge desire for openness and engagement and mutual learning with the rest of the world.

I was hired by a Party secretary called “Kong,” who's a 76th generation descendant of Confucius. They have a long family tree with very clear lineage, and they're very proud of that lineage. If you're part of that lineage, you could be buried in the Confucian cemetery in Qufu province which is the cemetery with the longest family history, I think, in the world.

He's a Party secretary who, literally, was responsible for the new campus in Qingdao. But he's also very proud of his Confucian tradition. He thought that I could help to both internationalize and promote Confucianism or to Confucianize the university — meaning, promote more Confucian teachings in the education and more engagements with the rest of the world about China's Confucian culture.